Staunch Prize Q&A

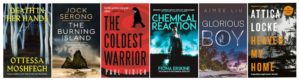

Staunch Prize Shortlist

Q&A with Paul Vidich and Bridget Lawless

Bridget: The introduction to The Coldest Warrior, where you describe the fallout from your uncle’s death and how it affected your extended family – is one of the most compelling prologues I’ve ever read. It’s a bold move to write a fictionalised account of such a death and cover-up. Did you feel a novel could have more impact than the print and screen journalism already dedicated to your uncle’s story?

Paul: Frank Olson’s death remains classified ‘undetermined.’ All print and screen accounts of the case stop at the precipice of knowledge—where the trail of evidence ends. The rules of journalism don’t reward speculation. In my novel, I was able to create a world that was not confined to the evidence. My novel offers one explanation of what happened. Undoubtedly, it is precisely wrong, but I believe that it is generally correct. I wrote The Coldest Warrior with the freedom that fiction enjoys to imagine the world beyond the precipice of knowledge. As Albert Camus said: “Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.”

Bridget: How did your family react to your publishing this story? Did you consult with family members about it?

Paul: Frank Olson has two living sons, both of whom I am close to. The older son, Eric, has been a tenacious investigator of his father’s murder for forty-five years, and he is the central figure in Erroll Morris’s documentary on the case, Wormwood, which appeared on Netflix two years ago. Eric was delighted to learn I would write a novel based on the case. I sent him an author review copy in advance of publication and, of course, I worried what he would think. I received a text the day he finished the novel – he loved it. I was relieved.

Bridget: With thrillers that focus on the suspicion that the CIA is at least in part ‘bad’, the investigator is usually in the comfortable position of being outside the field of blame. Jack Gabriel, a card-carrying member of the Agency seems surprised when he realises that yes, the CIA would kill one of their own – and that the major players are ‘untouchable’. Do you think much has changed since the ’70s when the novel is set?

Paul: The Frank Olson case is part of the legacy of inconvenient truths that exist in a democracy that finds it hard to balance openness with the need to keep secrets. This dichotomy continues to fascinate us. We love stories of the little guy challenging the powerful government and winning. The Report, the recent movie with Adam Driver, tells just such a story – the CIA trying to hide its record of torture from Congress. The UK movie Official Secrets addresses the same subject.

But this terrible stuff happens again and again. There are safeguards in the CIA against extra-judicial activity, but in a crisis, the safeguards are ignored, or new justifications are invented. This happened in the CIA’s efforts to kill Castro and Lumumba, it happened with the renditions of suspected terrorists after 911, it happened with America’s extreme interrogations in Afghanistan. Safeguards are conveniently set aside, or ignored, and extreme methods used.

There is a saying: In time of war, it is a soldier’s job to kill. We dress up the glory of war, but strip away the parades and the medals, and it’s that simple, a soldier’s job is to kill. In time of crisis, it’s the CIA’s job to lie, suborn allies, keep secrets, and if necessary, to kill – all in the name of national security. So, no, I don’t think anything has changed.

Bridget: The findings of the Rockefeller Report and the hearings you describe in the novel conjure images of the many men during the Trump administration, pleading ignorance or innocence from the dock as their deeds are uncovered. Much of what the CIA did during the 50s was justified by the cold war and only questioned with hindsight. Do you have any faith that we can hold our governments accountable faster, in a meaningful way, and with lasting consequences?

Paul: No. The pendulum swings in a narrow arc of accountability. A free press and free expression in art are the best protections we have against abuses of power.

Bridget: Wilson is murdered because he knows the truth, and if he reveals it, the world will be horrified. Because the truth, if known, would be unacceptable. He must die, unpalatable as that is, and to protect the secrets, it must be staged as suicide, with all that means to his family, friends and colleagues. The Agency can’t admit to despatching him because it’s expedient, so it chooses to make him look unstable. So is truth as much a victim as Charlie Wilson, or your uncle, when secretive agencies are at play it?

Paul: I give a character named Coffin a speech about truth: “Our Cold War was an artful victory of language. We used official language to create ambiguity, to shift meaning, and we used it to hide the truth.” And the book’s epigram is from George Orwell’s Politics and the English Language: “Political language…is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.” In many ways, the novel is about how language can be used to shape the past and turn lies into truths.

It is an urgent topic today in America. The Trump White House encourages the conflation of lies and truth, fact and opinion. In this way, we are more similar to Stalinist Soviet Union than we are to the America I grew up in. False stories create misinformation that engenders fear and hatred. The only difference between the Soviet Union’s treatment of truth, and Trump’s, is that the Soviet Union was also repressive – people were arrested, executed, families torn apart.

Bridget: I’m intrigued by the role of the women in this story – the wives – who know, but don’t want to know, what their husbands do. Women who understand they’re being lied to, who know not to ask, and somehow square it with themselves, become complicit, and enjoy the lifestyle. But Gabriel’s daughter Sara hasn’t made that pact with herself or her family. She’s kept in the dark until her father’s revealed to be working for the CIA. He’s ‘protected her from the truth’ without her permission. As she’s thrust into danger, because of him, do her innocence and disapproval force Jack to become a better man? Or does it simply give him the excuse to run?

Paul: Wives in the novel are complicit with their husband’s work, but they are also the novel’s moral conscience. They challenge their husbands. Jack Gabriel’s daughter, Sara, is also a counterpoint to Jack. Jack, his wife Claire, and Sara all are entangled in the crises. Spy novels usually ignore the family. But, I wanted to put a human face on the spy, as Graham Greene did in The Human Factor.

I wanted to show the psychological burdens of a man doing covert work who inevitably brings some of the darkness into himself, suffering the moral hazards of a job that sanctions lying, deceit, and murder. Gabriel’s wife makes him see the consequences of the agency’s darkness and that makes him a better man.

Bridget: Dare I ask what your hopes are for November 3rd? And the aftermath? Are they, indeed, hopes? Or do you predict more of the same, whoever’s in power?

Paul: By the time this answer is posted, we may know the results of the US election. Trump will go down in history as the worst American president. The crucible of history looks at character and accomplishment, and in Trump’s case, he has little of either. Leaders do make a difference. Churchill and Roosevelt were intelligent, courageous, and honorable. The world was a better place because of their leadership. It does matter who is in power.

Bridget: Who are your own writing heroes and heroines?

Paul: The Brönte sisters and Mary Shelley amaze me. They were young, Shelley only nineteen, when she wrote Frankenstein, which is a remarkable book for anyone to have written, but it boggles the imagination that it came from the imagination of a nineteen-year-old. And she suffered terribly in her life. I admire Shakespeare for the sheer brilliance of his plays.

Bridget: What are you working on now?

Paul: The Memorial Wall in the lobby of CIA Headquarters in Langley Virginia has 133 black stars carved into Vermont marble. Each star represents a fallen agency officer. Many are named, but some are identified only by the date and place they died. My next novel is about one man represented by an unnamed black star. The novel, due in March 2021, is called The Mercenary.